NYT: Economic Incentives Don’t Always Do What We Want Them To (h/t MR). For the first time in history, the title actually understates the article, which argues that incentives can be surprisingly useless:

Economists have somehow managed to hide in plain sight an enormously consequential finding from their research: Financial incentives are nowhere near as powerful as they are usually assumed to be.

The article starts with some surprising facts. Increased taxes on the rich don’t make rich people work much less. Salary caps on athletes don’t decrease athletic performance. Increased welfare doesn’t make poor people work less. Decreased job opportunities in one area rarely cause people to move elsewhere.

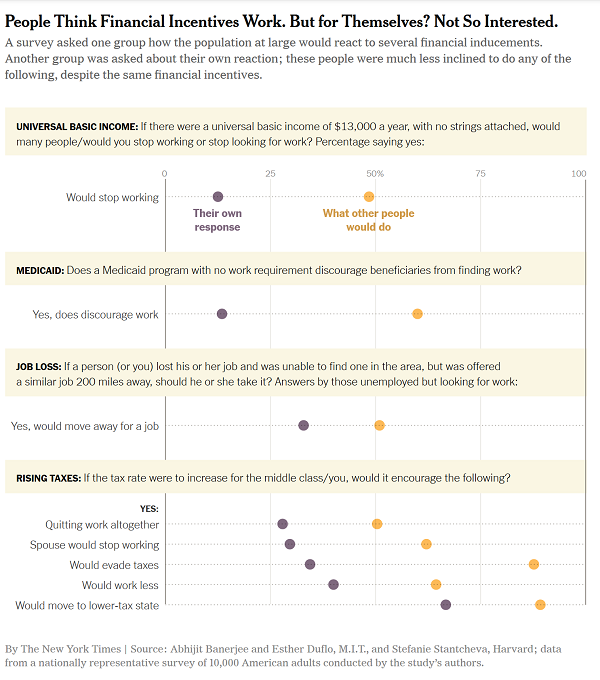

Then it presents a neat chart showing that most people believe others would respond to an incentive, but deny responding to that incentive themselves. For example, 60% of people say a Medicaid program with no work requirement would prevent many people from seeking work, but only 10% of people say they themselves would stop seeking work with such a program.

All this suggests that:

If it is not financial incentives, what else might people care about? The answer is something we know in our guts: status, dignity, social connections. Chief executives and top athletes are driven by the desire to win and be the best. The poor will walk away from social benefits if they come with being treated like a criminal. And among the middle class, the fear of losing their sense of who they are and their status in the local community can be an extraordinarily paralyzing force.

They conclude that this argues in favor of policies like raising taxes on the rich and removing all requirements from welfare programs.

The authors are Nobel Prize winning economists, so I assume they’re basically right. And I’m not up to doing a complicated literature review to compare all the cases where economic incentives do work to the cases where they don’t and develop a well-informed understanding of the subtleties in their position. So instead, a few low-effort thoughts.

First, it matters less whether the average person responds to economic incentives, and more whether the marginal person will. If I need someone to cover the graveyard shift at work, nobody will do it for normal pay, and I offer double pay, all I need is for one employee to be incentive-sensitive enough to take me up on it. Maybe most people wouldn’t accept any amount of money to become an oil rig worker, a McKinsey consultant, or a camgirl, but ExxonMobil/McKinsey/MyFreeCams.com only need just enough qualified people to accept whatever deal they’re offering.

Likewise, perhaps if I had no alarm system protecting my house, 99.999% of people still wouldn’t rob me. But 99.999% of people not robbing you is still known as “getting robbed”.

So “most people don’t respond to most economic incentives” is totally compatible with “economic incentives rule the world and control everything around us.”

Second, grant that most people care primarily about “status, dignity, [and] social connections”. A lot of how that works out in real life is “doing the socially acceptable thing”. Even if incentives are weak in the short term, they can be very strong in the long term after they have time to act on what is or isn’t socially acceptable.

It’s all nice and good to say “most people wouldn’t steal even in the absence of punishment”. But what about music piracy? Nobody had any way to enforce rules against pirating music. Maybe only a few people pirated at first. But then more and more people did it, and eventually the unwritten rule among teenagers became that music piracy was okay – in fact, that you were weird if you didn’t do it. On the other hand, stealing a CD from a record store still feels horrifying and criminal and inconceivable. Although there are subtle differences between the two cases (it costs nonzero money to make a physical CD) I still think a lot of this is social norms that formed downstream of enforcement-related incentives.

Or: most people would never cheat on welfare. But there are Alabama counties where over 25% of the population are on disability, an increase of 50% from just fifteen years earlier. I don’t want to accuse any of them of cheating, per se, and see here for a more in-depth analysis. But I think it’s easy to normalize taking disability for lesser and lesser afflictions, and that part of the normalization process involves an economic incentive to do it and a lack of incentive not to.

Or: in Sierra Leone, 84% of people say they have paid bribes; in Japan, 1% have. So do “people” care about financial incentives or not? Grant that “status, dignity, [and] social connections” are more important, and that this is what prevents bribery in Japan. But once these factors permit bribery, it becomes rampant. And are these factors themselves maintained partly by incentives, eg punishments upon being caught? I’m not sure.

Third, remember that principles are usually downstream of politics. So one fun game is to take a principle usually used on one side of the political spectrum, then apply it in support of the opposite side and see if you still hold it.

So. We know there’s no reason not to raise taxes, since rich people don’t respond to financial incentives. But there’s also no reason to close tax loopholes – rich people defrauding the government of money through tax evasion is surely as unthinkable as poor people defrauding the government through welfare scams. And there’s no reason to question the bonuses of Wall Street traders, since it’s not like anything as crass as a financial incentive would cause them to make risky trades.

Did pharmaceutical companies incentivize opioid overuse through paying doctors to overprescribe? Doesn’t matter, doctors would never let financial incentives affect their prescribing decisions. Are senators cozying up to companies that will give them lucrative sinecures later in a “revolving-door” system of legal bribery? No, because incentives aren’t powerful enough to make senators abandon their dignity. Are billionaires destroying the environment just to make a buck? No, the financial incentives to do so wouldn’t outweigh the cost in status and social connections.

None of this snark disproves the real empirical research the authors use to show that rich people’s taxes, poor people’s welfare use, and economic mobility are not very incentive-sensitive. But I hope they prevent people from generalizing to a general sense that financial incentives don’t matter, or turning this into a purely partisan issue where anyone who believes in financial incentives at all gets accused of “dog whistling” conservativism.

Fourth, and most important, the more we’re ruled by social incentives, the more importance financial incentives take on as a counterweight. Quoting my favorite part of the article again:

If it is not financial incentives, what else might people care about? The answer is something we know in our guts: status, dignity, social connections. Chief executives and top athletes are driven by the desire to win and be the best. The poor will walk away from social benefits if they come with being treated like a criminal. And among the middle class, the fear of losing their sense of who they are and their status in the local community can be an extraordinarily paralyzing force.

I think this is profoundly true, so true that it’s almost impossible to appreciate enough. The article frames it positively – we care about community more than money, how heartwarming. But I find it disquieting – it could equally be framed “We care more about fitting in and not seeming weird than about anything else in the world”. 99% of world-changing ideas are stillborn when their would-be-inventor worries they might sound weird for proposing them. 99% of great companies don’t get off the ground because their would-be-founder worries about what other people would think. The most important ideas for changing government and society sit on the lunatic fringe, because everyone worries that supporting such ideas might keep them out of the Inner Ring.

Paradoxically, I think this argues in favor of financial incentives. The beauty of financial incentives is that they provide a counterbalance to status incentives. The counterbalance is weak, inconsistent, blink-and-you-miss-it, but it is real. If all the cool people say “we do it this way”, 99% of people will do it that way to fit in, but there will be one person who does it the much better way that lets them outcompete everyone else and make $10 billion. And having $10 billion brings “status, dignity, [and] social connections” of its own. Even if only a tiny number of people are sensitive to money, it’s enough to create a core who occasionally try making things better even when that’s not cool.

One corollary of this is that when you remove financial incentives, you don’t get everyone acting ethically for the good of all. You just get status incentives with no counterbalance. I can think of few things scarier.